This is an additional article in the series on justice and race by Timothy Keller that includes: “The Bible and Race” (March 2020), “The Sin of Racism” (June 2020), and “Justice in the Bible” (September 2020).

The Problem We Face

Which justice? There have never been stronger calls for justice than those we are hearing today. But seldom do those issuing the calls acknowledge that currently there are competing visions of justice, often at sharp variance, and that none of them have achieved anything like a cultural consensus, not even in a single country like the US. It is overconfident to assume that everyone will adopt your view of justice, rather than some other, merely because you say so.

Biblical justice. In the Bible Christians have an ancient, rich, strong, comprehensive, complex, and attractive understanding of justice. Biblical justice differs in significant ways from all the secular alternatives, without ignoring the concerns of any of them. Yet Christians know little about biblical justice, despite its prominence in the Scriptures. This ignorance is having two effects. First, large swaths of the church still do not see ‘doing justice’ as part of their calling as individual believers. Second, many younger Christians, recognizing this failure of the church and wanting to rectify things, are taking up one or another of the secular approaches to justice, which introduces distortions into their practice and lives.

The History of Justice

The traditions. No one has done a better job of explaining our current predicament over justice than Alasdair MacIntyre, especially in his book Whose Justice? Which Rationality? [1] He shows that behind every understanding of justice is a set of philosophical beliefs about (a) human nature and purpose (b) morality, and (c) practical rationality—how we know things and justify true beliefs. In his book he traces out four basic historical traditions of justice. There is the Classical (Homer through Aristotle), the Biblical (Augustine through Aquinas, whose accomplishment was to incorporate some of Aristotle), the Enlightenment (especially Locke, Kant, and Hume)—which then set the stage for the modern Liberal approach, which has fragmented into a number of competing views that struggle with one another in our own day.

Earlier Enlightenment thinkers sought a basis for morality and justice not in God or religion but one that could be discovered by human reason alone. [2] David Hume did not believe that was possible. He argued that there are no moral norms or absolutes outside of us that we must obey regardless of what we think or feel, and therefore we cannot discover them through reason. Rather he taught that the only basis for our moral decisions was not reason but sentiment–moral intuitions grounded largely in our emotions rather than in our thinking. Hume “won the field” and today his successors have taken his ideas out to their logical conclusion, that all moral claims are culturally constructed and so, ultimately, based on our feelings and preferences, not on anything objective.[3][4]

The failure of the Enlightenment Project. But MacIntyre shows how problematic this is. The social consensus on morality and justice that Enlightenment thinkers thought they could achieve by leaving religion behind has not been realized, and MacIntyre explains why. In his famous wristwatch illustration, he shows it is impossible to determine if a watch is a “good” or a “bad” watch unless you know what it is for. Is it for hammering nails or telling you the time of day?[5] Without knowing the telos or purpose of the watch, any evaluation of it is impossible.

Likewise, unless you know what human beings are for, you will never come to any agreement as to what good or bad behavior is and therefore what justice is. The secular view is that human beings are just here through chance. We are not here for any purpose at all. But if that is the case then there is no good way to argue coherently on secular premises and beliefs about the world that any particular behavior is wrong and unjust. Human rights are based on nothing more than that some people feel they are important. Not everyone does, however, and what do you say to people who don’t believe in them and don’t honor them? Why should your feelings take precedence over someone else’s? After David Hume, no modern theory of justice has any answer other than–”because we say so.”

The Problem of Foundations

Many secular people respond to MacIntyre by saying we don’t need any basis for human rights, because “everyone knows” that care for the rights of others is just ‘common sense.’ Below is an excerpt from a dialogue interview (slightly edited by me) between Christian Smith, author of Atheist Overreach, and an atheist on a podcast called “Life After God.”

Smith: There is a difference between having an instinct that it is wrong to let people starve without helping them—it is another thing to insist that we ought to make the sacrifices—often huge sacrifices—necessary to prevent the suffering. If a people say: “[Why should we help others?] What happens beyond our borders is not our problem”–what does the [secular person] say to them?

The standard is not “do we have a regime to force people to sacrifice for others?” but do we have a basis for persuading a reasonable skeptic who asks “why should I care about them?” Do you have not only an explanatory rationale for why letting people starve is wrong–but also a justifying motivation so that they are motivated to make the sacrifices necessary to help them? Without both, you can’t have a set of moral values prevail in a society. And if you are [strictly secular] I don’t think you have them. I’m not saying atheists can’t choose to be good, but when they do so it is an arbitrary subjective preference, not a rationally grounded view that has persuasive power over others.

Atheist: That does not make sense to me. I just figure that because people are human beings that they should be treated fairly. I know what it feels like to be treated with kindness and with meanness. I know that others feel the same way, so I want to treat them with dignity and respect because that is what I would want. I don’t have an objective source for the dignity of people—it is based on the fact that I would want to be treated in this way. Why isn’t that compelling to a reasonable skeptic? Why do I need more reason/justification than that? It seems common sense.

Smith: I don’t think it is reasoning that is at work there. That’s not an argument–it’s a sensibility. And those kinds of sensibilities (about love and human rights) are riding on the continued currents of some millennia of a cultural inheritance that is powerfully influenced by Christianity and Judaism. That is what makes these ideals make sense to you. If I worry about anything—I worry about this. These moral ideals–of loving your neighbor and honoring her human rights regardless of who they are or where they are–make sense to us now. But if they are (as I think can be demonstrated) based on the cultural inheritance of religion [based on the worldview that our culture used to have], then will these moral ideals make sense to our grandchildren as religion continues to decline? Won’t they just ask: “Sure I care about my not-suffering, but why should I care about someone else’s not-suffering?” [Secularism] has no good answer to that question.

The atheist is saying to Smith that it is just common sense or rational to say, “I want to be treated this way, therefore I ought to treat others that way.” Smith says that is not reasoning. You may feel that the golden rule is right, but why should someone else feel the way you do about it?

A Brief Outline of Biblical Justice

In order to compare biblical justice to the secular alternatives, below is a brief outline of the facets of biblical justice.[6]

1. Community: Others have a claim on my wealth, so I must give voluntarily.

The Bible depicts the human world as a profoundly inter-related community. So the godly must live in such a way that the community is strengthened. Old Testament scholar Bruce Waltke puts all the teaching on “the righteous” in the book of Proverbs into a concise and practical principle: “The righteous (saddiq) are willing to disadvantage themselves to advantage the community; the wicked are willing to disadvantage the community to advantage themselves.”[7] The gleaning laws of the Old Testament are a case in point (Deuteronomy 24:17-22). Landowners were commanded to not maximize profits by harvesting all sheaves or picking all the olives or grapes. Instead the owner was to leave produce in the field for the workers and the poor to take through their labor, not through charity. When the text reads that the sheaves, olives, and grapes “shall be for” the poor, it uses a Hebrew phrase that indicates ownership. To treat all of your profits and assets as individualistically yours is mistaken. Because God owns all your wealth (you are just a steward of it), the community has some claim on it. Nevertheless, it is not to be confiscated. You are to acknowledge the claim and voluntarily be radically generous. This view of property does not fit well with either a capitalist or a socialist economy.[8]

2. Equity: Everyone must be treated equally and with dignity.

Leviticus 24:22- “You are to have the same law for the foreigner as for the native born.” The Hebrew word mesraim means equity and Isaiah 33:15 says “Those who speak with [equity, mesraim]…keep their hands from accepting bribes.” Bribery is unjust because in commerce, law, and government, it does not treat the poor the same as it does the wealthy. Any system of justice or government in which decisions or outcomes are determined by how much money parties have is a stench before God. Another example of inequity is unfair business practices. Leviticus 19:13 and Deuteronomy 24:14-15 speak of unfair wages. Amos 8:5-6 speaks of “unjust scales, selling even the sweepings with the wheat.” To cut corners and provide an inferior product in order to make more money but not serve customers is to do injustice.

3. Corporate responsibility: I am sometimes responsible for and involved in other people’s sins.

Sometimes God holds families, groups and nations corporately responsible for the sins of individuals. Daniel repents for sins committed by his ancestors even though there is no evidence he personally participated in them (Daniel 9). In 2 Samuel 21 God holds Israel responsible for injustice done to the Gibeonites by King Saul even though he was by that time dead. In Joshua 7 and Numbers 16, God holds whole families responsible for the sin of one member. In 1 Samuel 15:2 and Deuteronomy 23:3-8, he holds members of the current generation of a pagan nation responsible for the sins committed by their ancestors many generations before. Why? There are three reasons.

Corporate responsibility. Achan’s family (Joshua 7) did not do the stealing, but they helped him become the kind of man who would steal. The Bible’s emphasis on the importance of the family for character formation implies that the rest of the family cannot wholly avoid responsibility for the behavior of a member.

Corporate participation. Sinful actions not only shape us, but the people around us. And when we sin we affect those around us, which reproduces sinful patterns—even if more subtle—over generations. So, as in Exodus 20:5, God punishes sin down the generations because usually later generations participate in one form or another in the same sin.[9]

Institutionalized sin. Socially institutionalized ways of life become weighted in favor of the powerful and oppressive over those with less power. Examples include criminal justice systems (Leviticus 19:15), commercial practices such as high interest loans (Exodus 22:25-27; Jeremiah 22:13) and unfairly low (James 5:4) or delayed wages (Deuteronomy 24:14-15). Once these systems are in place, they do more evil than any one individual within the system may intend or even be aware of.

4. Individual responsibility: I am finally responsible for all my sins, but not for all my outcomes.

My outcomes. The Bible does not teach that your success or failure is wholly due to individual choices. Poverty for example, can be brought on by personal failure (Proverbs 6:6-7; 23:21), but it may also exist because of environmental factors such as famine or plague, or sheer injustice (Proverbs 13:23[10]; cf. Exodus 22:21-27). So we are not in complete control of our life outcomes.

My sins. Despite the reality of corporate responsibility and evil, the Bible insists that, ultimately, our salvation lies in what we do as individuals (Ezekiel 18). There is an asymmetrical balance between individual and corporate responsibility. Deuteronomy 24:16 says that in ordinary human law we must be held responsible and punished for our own sins, not those of our parents. We are indeed the product of our communities, but not wholly—we can resist their patterns. Ezekiel 18 is a case study of what can happen if we put too much emphasis on corporate responsibility—it leads to ‘fatalism and irresponsibility’[11]. The reality of corporate sin does not swallow up individual moral responsibility, nor does individual responsibility disprove the reality of corporate evil. To deny (or largely deny) either is to adopt one of the secular views of justice rather than a biblical one.[12]

5. Advocacy: We must have special concern for the poor and the marginalized.

While we are not to show partiality to any (Leviticus 19:15), we are to have special concern for the powerless (Isaiah 1:17; Psalm 41:1). This is not a contradiction. Proverbs 31:8-9 says “speak up for those who cannot speak for themselves…Defend the rights of the poor and needy.” The Bible doesn’t say “speak up for the rich and powerful,” not because they are less important as persons before God, but because they don’t need you to do this. The playing field is not level and if we don’t advocate for the poor there will not be equality. In this aspect of justice, we are seeking to give more social, financial, and cultural capital (power) to those with less. Jeremiah 22:3 says “Protect the person who is being cheated from the one who is mistreating… foreigners, orphans, or widows…” Jeremiah is singling out for protection groups of people who can’t protect themselves from mistreatment the way others can. (cf. Zechariah 7:9-10)

The Spectrum of Justice Theories

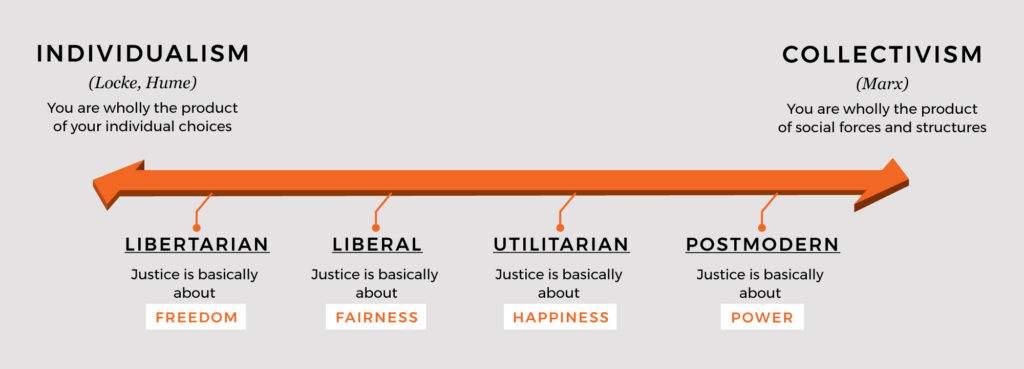

In briefly outlining the alternative accounts of justice operating in our culture, some oversimplification is unavoidable.[13] Still, there is widespread agreement that something like the following four categories of justice theories are operating.[14]

All the theories on this spectrum are secular, sharing two assumptions. (a) First, unlike Martin Luther King, Jr. (see “Letter from Birmingham Jail”) they all assume that there are no transcendent, moral absolutes on which to base justice. They believe in Taylor’s “immanent frame,”[15] that there is no supernatural reality and so moral values and the definition of justice itself are invented by human beings. (b) They all see human nature as a blank slate that can be wholly reshaped by human means, not as a God-given nature that must be honored for us to thrive.

1. Libertarian – “Freedom” A just society promotes individual freedom.

This view, recently argued by Robert Nozick, believes in a small number of individual rights, but not entitlements. Persons have the right to not be harmed, an absolute right to private property if fairly earned, and to the rights of free speech and free association. The first way to guard these rights is to have small government, since high taxes are unjust, a violation of the right to private property, and large-scale government inevitably seeks to regulate speech, thought, and association.

The second way to guard these rights is to have an unregulated free market. The Libertarian view is highly individualistic, based on the implicit assumption that every human being belongs to him or herself, and that the outcomes of anyone’s life depend wholly on their individual choices and efforts.[16]

Quick biblical analysis:

First, this view denies the complexity of who we are—individuals yet embedded in communities instituted by God (family, state) and created in the image of a Three-in-One God. The Bible balances individual freedom with community obligation. Unlike the Bible, Libertarianism denies or downplays the role of oppressive social forces in what makes people poor, refusing to see how sin creates un-level playing fields that mere individual freedom cannot remedy.

Second, it denies the doctrine of the universality of sin. It sees the evil capacities of government but not so much of capital markets, though human sin is everywhere and will corrupt everything.

Third, it has a sub-biblical understanding of freedom. Libertarianism usually sees freedom in wholly negative terms—it is freedom from. But we were created by God for loving him and our neighbor, not just self-interest, and so the more we do what we were created to do the more free we will be.

Finally, this view’s understanding of absolute rights over property and over self does not square with the Bible’s view of creation. We belong to God, not to ourselves, and so does everything we own. Whatever we have is ultimately God’s gift and must be shared.

2. Liberal – “Fairness” – A just society promotes fairness for all.

This view, more recently argued by John Rawls, greatly expands the idea of human rights into (what Libertarians would call) entitlements.[17] Liberals add to freedom rights (right to speech, property, religion) also social or “economic rights” (right to an education, to medical care).[18] Rawls’ justification for such rights goes like this. He argued that if people had to devise a society from behind a “veil of ignorance”—not knowing where they would be placed (not knowing what race, gender, social status, etc. they would be)—that everyone would, out of pure, rational self-interest, design one in which there were significant legal measures to redistribute wealth to those who were born in poor communities and to establish many other economic and social rights. Only that kind of society would be fair and rational. Once it is established that economic and social rights are valid, then, in the Liberal view, there is no need in society for any consensus on moral values–no need to all agree on what the Good is. Rather, honoring individual human rights becomes the only necessary moral standard (and denying them the only sin). Then people will be free to live their lives pursuing whatever they believe is their good.

A major difference from the Libertarian view is that now it is just and fair for the State to redistribute wealth through taxation and government control of the market. Nevertheless, Rawls and liberals still believed that some kind of free market was the best way to grow the wealth of a society that then can be shared justly. The reason that Liberals are basically still friendly to capitalism is that ultimately this view is still highly individualistic, giving individuals freedom to create their own “good” and meaning and morality. So Liberalism still aims not for equal outcomes but equal opportunity for individuals to achieve their happiness. Individual outcomes are still seen as determined by individual efforts and work ethic.

Quick biblical analysis:

As much recent scholarship has demonstrated, Liberalism’s beliefs in human rights and care for the poor are grounded in Christianity.[19] The scholars argue that these beliefs depend on a view of the individual as having infinite dignity and worth and of individuals as being equal regardless of race, gender, and class. This belief only arose in cultures influenced by the Bible and marked by a belief in a Creator God. They also show that these Judeo-Christian beliefs do not fit with the modern secular view that there are no moral absolutes and that humanity is strictly the product of evolution. The conclusion is that these older beliefs in human dignity are essentially smuggled into secular modern culture. This means that Christians can agree with much in this justice theory. Nevertheless, as MacIntyre showed, there are contradictions and fatal flaws in Liberalism’s approach.

First, the freedom of the individual has become a de facto absolute that vetoes all other things and, unlike in more traditional societies, liberal societies have not been able to balance individual freedom and obligation to family and community. The result has been the dissolution of families, neighborhoods, and institutions. It turns out that, without a set of shared moral values (besides a commitment to individual freedom), and without a shared story of who we are corporately as people, a society cannot keep from fragmenting. Because Liberalism has been the dominant justice theory, the current tribalism, unprecedented loss of social trust, and breakdown of institutions can be seen as a failure of Liberalism. Some argue that Liberalism “worked” in a society only when religion remained strong, because it could offset the selfishness that individualism fosters and it could provide the sense of solidarity and community that individualism cannot give. Now that religion is in sharp decline, that balance is gone.[20]

Second, if justice is just honoring individual rights and entitlements and there are no higher moral absolutes, how can we adjudicate matters when rights-claims conflict and contradict as they so often do? Another problem with Liberalism is that people’s rights-claims often contradict. Liberalism has no way to determine if some rights may take precedence over others. In the feminists vs. transgender debate, who wins and on what basis? Loudest voice, most money?

Third, even secular critics point out that rationality is an insufficient basis for a fair society. Many critics of Rawls have observed that if your only motivation is rational self-interest, those behind the “veil of ignorance” would still not have to agree to entitlements. The number of poor is a minority—and chances are, you won’t be one. So why not take a risk by setting up a society that exploits the poor to advantage the rest of society? Why not opt for that as long as you aren’t likely to be poor yourself? Exploiting the poor then can definitely be seen as “rational self-interest.” But if Liberals want to respond that exploiting the poor is wrong they have taken away their right to do that, because they deny moral absolutes. Who is to say that exploiting the poor might not be, in a cost-benefit analysis, more practical than not? There are, then, no real guardrails to keep a liberal society from moving toward oppression.

Finally, Liberals’ insistence that religious views stay out of public discourse is hypocritical. It tells religious people they must not argue from their faith-beliefs but only use ‘public reason’ and ‘rational self-interest’—all the while smuggling in their own beliefs on human nature, rights, sexuality, and many other things that are faith-assumptions, left over from our Christian past, and not the deliverances of science.

3. Utilitarian – “Happiness” A just society maximizes the greatest happiness for the greatest number.

This third theory, associated with John Stuart Mill, is not as influential in formal jurisprudence and yet its basic idea makes a great deal of intuitive sense to secular people. Arguably, utilitarianism dominates most public discourse over public policy, and lies behind many individual justice claims. In this view the essence of justice is the greatest happiness for the greatest number. This is another effort to have justice grounded not in moral absolutes but in some kind of “practical rationality.” If something makes the majority of people happy, then it is just. But where are the guardrails? Does it mean that anything the majority desires for happiness is ok? Utilitarians use the “harm principle” to create limits. They argue that people should be free to pursue whatever makes us happy as long as it doesn’t harm others. It is obvious, however, that there will be inevitable clashes over what makes people happy and so the final arbiter for Utilitarians is majority rule. Today, the news media relies heavily on utilitarianism when it argues, explicitly or implicitly, that polls tell us that most Americans now favor X—and therefore X is now OK. Utilitarianism is not as individualistic as the first two theories of justice—it is ‘majoritarian’. Indeed, many Utilitarians see individual rights as barriers to majority happiness. “If you believe in human rights, you are probably not a utilitarian”.[21]

Quick biblical analysis:

First, without a doctrine of creation, this view does not honor individuals as having a dignity that must not be violated. Could the majority of a national populace define their happiness in such a way that it can only be achieved if a minority of the population is put in internment camps? On the premises of Utilitarianism, that could easily be argued (and it was, in Nazi Germany and even in the U.S. with regard to Japanese-Americans during World War II).

Second, without a doctrine of sin, it naively assumes that what will make a majority happy can’t be something evil. Just because something makes a person happy, it doesn’t mean it is right to do it. Lots of foolish and cruel things can make us happy. Also, without an understanding of humans as souls and bodies, this view assumes “happiness” can be delivered by providing material goods and wealth and pleasures, when long wisdom across the cultures has recognized that this is inadequate for real happiness.

Finally, the “harm principle” is useless as any guide or as a barrier to abuse. The moment you say something is harmful, you are rooting your statement in some view of human nature—how human beings ought to live—and in some understanding of right and wrong. To say that something doesn’t harm anyone is based on some view of human nature and human purpose that is ultimately a matter of faith. Defenders of Jim Crow laws often used utilitarian arguments and the harm principle, telling African-Americans that segregation was not harmful, but was for their good. Without any moral absolutes—who is to say what is good for a minority? The majority–not the minority–gets to define it.

4. Postmodern–“Power” A just society subverts the power of dominant groups in favor of the oppressed.

The fourth justice theory in some ways is the newest on the scene, though it has an older pedigree. Drawing on the teaching of Karl Marx, what can be called postmodern Critical Theory has emerged very recently with its own account of justice which is sharply different from the others.[22] Because it has taken shape more recently and has come on the scene so forcefully, we will take more time to describe and interact with it.[23]

Postmodern critical theory argues:

First, the explanation of all unequal outcomes in wealth, well being, and power is never due to individual actions or to differences in cultures or to differences in human abilities, but only and strictly due to unjust social structures and systems. The only way to fix unequal outcomes for the downtrodden is through social policy, never by asking anyone to change their behavior or culture.[24]

Second, all art, religion, philosophy, morality, law, media, politics, education and forms of the family are determined not by reason or truth but by social forces as well. Everything is determined by your class consciousness and social location. Religious doctrine, together with all politics and law are always, at bottom, a way for people to get or maintain social status, wealth, and therefore power over others.

Third, therefore, reality is at bottom nothing but power. And if that is the case, then to see reality, power must be mapped through the means of “intersectionality.” The categories are race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity (and sometimes others). If you are white, male, straight, cisgender then you have the highest amount of power. If you are none of these at all, you are the most marginalized and oppressed–and there are numerous categories in the middle. Most importantly, each category toward the powerless end of the spectrum has a greater moral authority and a greater ability to see the way truly things are. Only powerlessness and oppression brings moral high ground and true knowledge. Therefore those with more privilege must not enter into any debate—they have no right or ability to advise the oppressed, blinded as they are by their social location. They simply must give up their power.

Fourth, the main way power is exercised is through language—through “dominant discourses.” A dominant discourse is any truth-claim, whether grounded in supposed reason and science or in religion and morality. Language does not merely describe reality—it constructs or creates it. Power structures mask themselves behind the language of rationality and truth. So academia hides its unjust structures behind talk of “academic freedom,” and corporations behind talk of “free enterprise,” science behind talk of “empirical objectivity”, and religion behind talk of “divine truth”. All of these seeming truth-claims are really just constructed narratives designed to dominate and, as such, they must be unmasked. Reasoned debate and “freedom of speech” therefore is out—it only gives unjust discourses airtime. The only way to reconstruct reality in a just way is to subvert dominant discourses—and this requires control of speech.

Fifth, cultures, like persons, can be mapped through intersectionality. In one sense no culture is better in any regard from any other culture. All cultures are equally valid. But people who see their cultures as better, and judge other cultures as inferior or even people who see their own culture as “normal” and judge other cultures as “exotic”, are members of an oppressive culture. And oppressive cultures are (though this word is not used) inferior—and to be despised.

Finally, neither individual rights nor individual identity are primary. Traditional liberal emphasis on individual human rights (private property, free speech) is an obstacle to the radical changes society will need to undergo in order to share wealth and power. And it is an illusion to think that, as an individual, you can carve out an identity in any way different or independent of others in your race, ethnicity, gender, and so on. Group identity and rights are the only real ones. Guilt is not assigned on the basis of individual actions but on the basis of group membership and social/racial status.

Quick biblical analysis:

First, it is deeply incoherent. If all truth-claims and justice-agendas are socially constructed to maintain power, then why aren’t the claims and agendas of the adherents of this view subject to the same critique? Why are the postmodern justice advocates’ claims that “This is oppression” unquestionably, morally right, while all other moral claims are mere social constructs? And if everyone is blinded by class-consciousness and social location, why aren’t they?[25] Intersectionality claims oppressed people see things clearly—but why would they if social forces make us wholly what we are and control how we understand reality? Are they less formed by social forces than others? And if all people with power—who “call the shots” socially, culturally, economically, and control public discourse—inevitably use it for domination, then if any revolutionaries were able to replace the oppressors at the top of the society, why would they not become people that should subsequently be rebelled against and replaced themselves? What would make them different? The Postmodern account of justice has no good answers for these questions. You cannot insist that all morality is culturally constructed and relative and then claim that your moral claims are not. This is not a flaw that only Christians can see, and this may therefore be a fatal flaw for the entire theory.[26]

Second, it is far too simplistic. The postmodern view of justice follows Rousseau and Marx, who saw human beings as inherently good or blank slates. Any evil is instilled in us by society, by social systems and forces. So any pathology (poverty, crime, violence, abuse) is due to one thing only- wrong social policy. But biblically we know we are complex beings–socially (both individual and social creatures made in the image of a Three-in-One God), morally (both sinful and fallen, yet valuable in the image of God), and constitutionally (we are equally soul-spirit and body). The reasons for evil and for unjust outcomes in life are multiple and complex.

So, for example, the restoration of a poor community will require a rich, multi-dimensional understanding of human flourishing. There certainly is a need for social reform and the dismantling of systemic injustice. But people also need meaning in life, and strong families, and ways to grow in character, and healthy, functional communities, and moral discipline as well. This view ignores the complexity of what makes humans thrive and therefore its programs will not actually work to liberate oppressed people. It ignores too much of what makes us human.

Third, it undermines our common humanity. Biblically, we are primarily individuals before God, made in his image, and secondarily members of a race/nationality. The postmodern view, however, makes one’s racial or group identity primary, superseding all loyalties to the nation or to the human race as a whole. This comes close to saying that there are humanities rather than a common, human race.

And therefore, fourth, it denies our common sinfulness. The Bible teaches that sin is pervasive and universal. We are each members of a race or nationality that contains much unique common grace to contribute to the world. But every culture also comes with particular sinful idolatries. No race or people group is inherently more sinful than others. But in this postmodern view of justice groups are assigned higher or lower moral value depending on their power, and some groups are denied any redeeming characteristics at all. To see whole races as more sinful and evil than other races leads to things like the Holocaust.

Fifth, it makes forgiveness, peace, and reconciliation between groups impossible. Miroslav Volf writes: “Forgiveness flounders because I exclude the enemy from the community of humans even as I exclude myself from the community of sinners.”[27] Without using the word “sin”, the adherents of this view continually do what Volf describes. So reconciliation flounders.

Sixth, it offers a highly self-righteous ‘performative’ identity. The Christian identity is received from God’s gracious hands, not achieved by our actions—we are loved absolutely apart from our performance. Contrarily, this view provides two kinds of identity that are highly perfomative: either being a member of an oppressed group fighting for justice or a white ally anti-racist. Both identities—like all other identities not based in Christ—can produce anxiety because of the need to prove oneself sufficiently justice-oriented. The secure identity of Christians does not require shaming, othering, and denouncing (which is always a part of a highly performative identity). Also, the new Christian identity—that we are simultaneously sinful and infinitely loved—changes and heals former oppressors (by telling them they are just sinners) as well as former oppressed (by assuring them of their value). See James 1:9.

Finally, it is prone to domination. This theory sees liberal values such as freedom of speech and freedom of religion—as mere ways to oppress people. Often this view puts these “freedoms” in scare quotes. As a result, adherents of this theory resort to constant expressions of anger and outrage to silence critics, as well as to censorship and other kinds of social, economic, and legal pressure to marginalize opposing views. The postmodern view sees all injustice as happening on a human level and so demonizes human beings rather than recognizing the evil forces–“the world, the flesh, and the devil”–at work through all human life, including your own. Adherents of this view also end up being utopian — they see themselves as saviors rather than recognizing that only a true, divine Savior will be able to finally bring in justice. When dealing with injustice we do confront human sin, but in addition “we wrestle not [merely] with flesh and blood” (Ephesians 6:12).

Comparing Biblical Justice to the Alternatives

First, only biblical justice addresses all the concerns of justice found across the fragmented alternate views.[28] Each secular theory of justice addresses one or some of the five facets of biblical justice mentioned above, but none addresses them all.

Second, biblical justice contradicts each of the alternate views neither by dismissing them nor by compromising with them. (a) Biblical justice is significantly more well-grounded. It is based on God’s character—a moral absolute—while the other theories are based on the changing winds of human culture. (b) Biblical justice is more penetrating in its analysis of the human condition, seeing injustice stemming from a more complex set of causes—social, individual, environmental, spiritual—than any other theory addresses. (c) Biblical justice provides a unique understanding of the character of wealth and ownership that does not fit into either modern categories of capitalism or socialism.

Third, biblical justice has built-in safeguards against domination. As we have seen, to have a coherent theory of justice, there must be the affirmation of moral absolutes that are universal and true for all, in all cultures. Without appealing to some kind of non-socially constructed truth and morality, there is no way to further justice.[29] Yet the French postmodernists were right—in the hands of human beings, truth-claims tend toward totalitarianism or at least the forces of domination readily use them. But Christianity offers truth-claims that can subvert domination. How?[30] (a) Christianity does not claim to explain all reality. There is an enormous amount of mystery – things we are simply not told (Deuteronomy 29:29). We are not given any ‘theory of everything’ that can explain things in terms of evolutionary biology or social forces. Reality and people are complex and at bottom mysterious. (b) Christianity does not claim that if our agenda is followed most of our problems will be fixed. Meta-narratives have a “we are the Saviors” complex. Christians believe that we can fight for justice in the knowledge that eventually God will put all things right, but until then we can never expect to fully fix the world. Christianity is not utopian. (c) Finally, the storyline of the whole Bible is God’s repeated identification with the wretched, powerless, and marginalized. The central story of the Old Testament is liberation of slaves from captivity. Over and over in the Bible, God’s deliverers are usually racial and social outsiders, people seen to be weak and rejected in the eyes of the power elites of the world.

Fourth, only biblical justice offers a radically subversive understanding of power. The Postmodern view rightly critiques the Liberal and other secular views as being blind to the operations of power and oppression at work in human life and society. Liberals rightly criticize the Postmodern for being prone (and blind) to its own forms of domination. Biblical justice, in contrast with the Liberal, gives us a profound account of power and its corruptions, but in contrast to the Postmodern, gives us a model for changing how it is used in the world.

When God came to earth in Jesus Christ he came as a poor man, to a family at the bottom of the social order. He experienced torture and death at the hands of religious and government elites using their power unjustly to oppress. So in Jesus we see God laying aside his privilege and power—his “glory”—in order to identify with the weak and helpless (Philippians 2:5-8). And yet, through the endurance of violence and human injustice he paid the rightful penalty of humanity’s sin to divine justice (Isaiah 53:5). Then he was raised to even greater honor and also authority to rule (Philippians 2:5:9-11). Jesus takes authority, but only after losing it in service to the weak and helpless.

So the Bible does not presume an end to the “binary” of power. Rule and authority are not intrinsically wrong. Indeed, they are necessary in any society. But while not ending the binary, neither does Christianity simply reverse it. It does not merely fill the top rungs of authority with new parties who will use power in the same oppressive way that is the way of the world.

Because it is rooted in the death and resurrection of Jesus, Christianity neither eliminates nor merely reverses the ruler/ruled binary—rather, it subverts it. When Jesus saves us through his use of power only for service, he changes our attitude toward and our use of power.[31]

There is nothing in the world like biblical justice! Christians must not sell their birthright for a mess of pottage. But they must take up their birthright and do justice, love mercy, and walk humbly with their God (Micah 6:8).

Article Footnotes

[1] See Alasdair MacIntyre, “Justice as Virtue: Changing Conceptions” Chapter 17 in After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory, 3rd edition, University of Notre Dame Press, 2012 and Whose Justice? Which Rationality? University of Notre Dame Press, 1988.

[2] The history of the Enlightenment is complex, and most historians speak of “Enlightenments” in the plural. All Enlightenment thinkers sought to establish moral values on the basis of reason alone, without recourse to religion, as a way to help people live in peace in a country despite different religious beliefs. John Locke was a professing Christian who believed in God and in ‘natural law’–moral truths embedded in the universe. But he was part of the Enlightenment project, namely, to show that all those moral truths of God could be deduced by reason alone. So while John Locke can be said to be one of the main authors of our modern western individualism, he can’t directly be charged with our secularism. For more on the corrosiveness of the individualism Locke bequeathed to us, see Robert Bellah, et al, Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life (With a New Preface), University of California Press, 2008.

[3] Hume was not himself a moral relativist. He did not say “you have your truth and morality and I have mine.” He believed moral truths, while not objectively true independent of our feelings and intuitions, still end up having a kind of stability because he thought that people’s feelings about right and wrong almost completely agreed. And because we so widely agree, for example, that murder is wrong—then we can say it is wrong even if a particular individual might feel otherwise. But the problems with Hume’s view are enormous. First, if the only basis for morality is that our shared moral feelings and intuitions align—what happens when they do not? After Hume there is now no going back to “reasoning together”—either via the principle of self-interest or by deduction from natural law. Secondly, if the only basis for morality is the majority of human sensibilities, then how do you ever call out a majority for injustice to a minority? If slavery was acceptable to most people’s moral intuitions (and it was for thousands of years), then there could not have been anything objectively wrong with it. And on what basis could anyone say to the majority—“This is wrong and should stop”? If Hume is right, there is no basis for a movement of justice like that. In the end, on Hume’s premises, morality does indeed become relative.

[4] For more on the Enlightenment and morality: In our time there has been an effort by many secular people to find a basis for morality that is not rooted in religion but nevertheless does not end in a relativism based just on our feelings. The project has been to find a scientific, empirical basis for morality. But this effort has not succeeded at all. See James Davison Hunter and Paul Nedelisky, Science and the Good: The Tragic Quest for the Foundations of Morality, Yale, 2018. See also Christian Smith, Atheist Overreach: What Atheism Can’t Deliver, Oxford, 2018. Finally, for a brief overview, see Philip Gorski, “Where Do Morals Come From?” Public Books, February 15, 2016.

[5] MacIntyre, After Virtue, 57-59.

[6] As said, this is only a brief outline. We may be able to post an article giving a much fuller biblical-theological account of justice soon.

[7] Bruce K. Waltke, The Book of Proverbs: Chapters 1-15, Eerdmans, 2004, 97. The earlier quote is by Waltke citing J.W. Olley.

[8]The Jubilee year (Leviticus 25), the gleaning laws, and the very definition of saddiq (“righteousness”) “suggest a sharp critique of [both] 1) the statism that disregards the precious treasure of personal rootage, and 2) the untrammeled individualism which secures individuals at the expense of community.” Craig Blomberg, Neither Poverty Nor Riches, Apollos, 1999, 46

[9] See how the harmful favoritism Abraham showed between his sons was reproduced both in Isaac and in Jacob, to terrible effect. (Genesis 12-50)

[10] Proverbs 13:23- “The unplowed field of poor people yields plenty of food but their existence is swept away through injustice” Waltke, 549-550. “The unplowed field…yields” refers to land so productive that it produces fruit even when not plowed. “…plenty of food” means that the poor are working hard to harvest it. So then why are they poor? “…their existence is swept away through injustice [Heb lo mishpat]”. Here then are three possible causes of poverty—environmental, personal, and social. According to Proverbs, sometimes poverty is caused by poor resources, sometimes by personal irresponsibility. But here we see that poverty can be caused by sheer injustice, without any blame on the poor at all.

[11] John B. Taylor, Ezekiel: An Introduction and Commentary, Tyndale, 1969, 147.

[12] For centuries biblical scholars have recognized the balance between corporate and individual responsibility in the Bible. For several decades there was a view that God only dealt with Israel on a corporate basis, never individually, and that therefore Ezekiel 18:1-32 was an innovation. See Gordon Matties, Ezekiel 18 and the Rhetoric of Moral Discourse, Society of Biblical Literature, 1990, for more on this debate. That view is largely abandoned now as too simplistic. See Daniel Isaac Block, The Book of Ezekiel, Chapters 1–24, Eerdmans, 1997, p. 556. To begin with, earlier texts such as Deuteronomy 24:16 demanded that judges not hold people responsible for their parents or children’s sins. Today, therefore, most scholars understand that there is both corporate and individual responsibility for sin in the Bible. Despite this long history of interpretation, there are many today who continue to insist that any Bible teacher talking about corporate sin and responsibility at all is reading modern liberal or Marxist ideas back into the Bible. Sometimes they concede that Israel was often judged corporately, but they argue that God does not do that with the rest of us. This ignores the fact that God does hold other nations responsible for the sins of their ancestors as well (Deuteronomy 23:3-4; Amos 1:1-2:5). So we cannot conclude that any Bible teacher talking about systemic injustice or corporate sin must be imposing secular ideas on the text.

[13] And we must keep in mind that justice theories are not necessarily political categories. Both political conservatives and political liberals can inhabit any of the first three, for example.

[14] I am basically following Michael Sandel, who in Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2009, lists four theories of justice – Libertarianism (Robert Nozick), Utilitarianism (John Stuart Mill), Liberalism (Kant/John Rawls), and Virtue ethics (Aristotle/MacIntyre). I’ve not treated Virtue ethics and this school’s theory of justice because, while it has traction among some intellectuals, it is not presently culturally influential. In its place I put Identity Politics, based on postmodern critical theory. This is a very influential new player on the field that was not so prominent when Sandel wrote. So my four are – Libertarian, Liberal, Utilitarian, and Postmodern. I explain in a footnote below why I think it is fair to call the last view Postmodern.

[15] Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, Harvard, 2007.

[16] “Lockean” natural rights are the right to life, liberty, and private property. In John Locke’s Second Treatise of Government, he argued that people have a right to have their physical lives protected and preserved, to be free to choose how they want to live if they don’t impede the freedom of others, and the right to property. This included not only private property but, Locke argued, every person owns himself. Some argue that these are “negative rights” because, as formulated, they are mainly the right to not have certain things happen to us (e.g. murder, prison without trial, theft, over-regulation of behavior).

[17] Sandel sees Rawls’ view as being built on the concept rights argued by Immanuel Kant, who has a far more robust understanding than Locke did. (Sandel, Justice, 140) Kant’s “Categorical Imperative,” that insisted every individual by virtue of being rational creatures, had to be treated “not as a means to an end but as an end in itself.” Many have pointed out that this is basically a version of Christianity’s doctrine of the image of God, yet it falls short of that. Any concept of rights grounded in identified capacities (like rationality or ability to make choices) opens one to the claim that some people (senile people, infants, disabled people) who lack the identified capacity has no rights. See Nicholas Wolterstorff, Chapter 15- “Is a Secular Grounding of Human Rights Possible?” in Justice: Rights and Wrongs, Princeton, 2010, 223-241.

[18]For an example of the clash over “economic and social rights” see the recent controversy over Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s Commission on Unalienable Rights. The commission prioritized “Lockean” rights–freedom of speech, religion, and the rights of private property over social and economic rights. The mainstream press reacted with shock. But the controversy is nothing but the latest version of the old debate between Robert Nozick and John Rawls over what counts as “rights”. Without understanding the ideological and historical background the journalists could not make sense of what was happening. See New York Times, July 16, 2020 “Pompeo Says Human Rights Policy must Prioritize Property Rights and Religion”. Found at https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/16/us/politics/pompeo-human-rights-policy.html

[19] See Taylor, A Secular Age and Larry Siedentop, Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism, Harvard, 2014 as just two examples. In the last few years these scholars plus Philip Gorski of Yale, Eric Nelson of Harvard, and many others, have argued that Christian beliefs are the sources of western liberalism’s values of human rights and care for the poor. More recently Tom Holland, Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World, Basic Books, 2019 has summarized much of this scholarship in a long but popularly written book. Of course it was Friedrich Nietzsche who originally argued that, without belief in the Christian God there is no basis for belief in equal human rights and dignity, and that all liberals who maintain such values are really still being Christian (at least in this part of their thinking) without acknowledging it.

[20]The classic case for this idea is made by Robert Bellah, et al, Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life; With a New Preface, University of California, 2008.

[21] Sandel, 103.

[22] The history behind this theory of justice finds the fusing of several important streams or schools of thought. It begins with the teachings of Karl Marx that all reality is determined by social forces, and therefore not only our behavior but our beliefs about truth and morality are determined by our class consciousness. But Marx used this basic radical idea almost wholly to critique economics, class, and economic systems. In the 20th century architects of “modern critical theory” such as Adorno and Marcuse began applying this Marxist analysis to a critique of culture in all its forms. Their goal was to make visible the hidden operations of power that the bourgeois used to keep the proletariat oppressed—not through force of law as much as through the power of culture, art, story. Later, French postmodernists such as Derrida, Foucault, and Lyotard became even more radical, reflecting extensively on the instability of language and concluding that any truth-claim at all was a move of power. That meant that now there was nothing left of reality but power. These original French postmodernists, however, were highly skeptical about social reform and assumed that any theory of justice would itself become a tool of oppression. (They rejected classical Marxism for that very reason.) One of the reasons for their deep skepticism was a consistency of thought. If all truth claims and grand visions are ways of oppressing people, then no one making claims about right and wrong, justice and injustice, will be able to escape doing this same oppression, no matter how well-intentioned. Who is to say what truth and justice is, anyway? Everything we do and say exerts power over people. So the best thing to do is to just carve out a bit of freedom for yourself and others by deconstructing all grand visions and by being a self-created individual and by staying detached from all movements. Despite this view of the original postmodernists, a number of thinkers especially in the American academy in the late 1980s and 1990s (Derrick Bell, Kimberle Crenshaw, Judith Butler and many others) accepted what the French postmodernists said about power and truth, but did not apply to themselves (as the original postmodernists did). Rather, they brought a more positive view of socialism together with postmodernism into what has been called “Postmodern Critical Theory”. It is a strategy for radical social change that not only seeks to overturn traditional and religious views but also secular, individualistic liberalism itself.

[23] For more on how contemporary schools of thought develop from older ones: Charles Taylor in A Secular Age shows how modern secularism grew out of the Enlightenment and other older movements not in a direct line but by “zig-zags”, ironies, and unintended consequences. So Marxism is not the same as the neo-Marxist critical theory of the Frankfurt School nor is that the same as the French post-structuralists, nor are they the same as postmodern critical theorists after 1989. Each group was highly critical of the others. Marxists like Terry Eagleton are highly critical of post-structuralists such as Foucault and Derrida (see his The Illusions of Postmodernism, 1996) and Derrida rejects classical Marxism in Specters of Marx, 1993). Yet the links between these movements are also widely acknowledged. Even inside the volume Specters of Marx, Derrida says that “Deconstruction…is also to say in the tradition of a certain Marxism, in a certain spirit of Marxism” and “one must assume the heritage of Marxism.” So Taylor is right about “zig-zags”. One more example: Taylor shows how post-structuralism, or what he calls “the immanent counter-enlightenment”, is as much if not more the fruit of Nietzsche as Marx, even though Nietzsche despised Marxism. For more on how post-structuralism was taken up—discarded in some ways but adopted in some ways—by later critical theory, see Walter Truett Anderson, The Truth About the Truth, Putnam, 1995, later issued in an abridged form as The Fontana Postmodern Reader, Fontana, 1996.

[24] For an interesting example of the “all inequalities are due to social forces” ideology, read Ibram X. Kendi “Stop Blaming Young Voters for Not Turning Out for Sanders” The Atlantic, March 17, 2020. Kendi addresses a perennial issue, namely, that older people vote in much larger numbers than younger people. This has been the case for many generations, and most observers have attributed this to more inward factors. Younger adults are more mobile and tend to be less rooted and committed to a particular locality, ‘youth culture’ doesn’t put the same emphasis on it—and so on. Kendi refuses to posit any influence to personal or cultural factors at all. All differences in outcomes must have to do with ‘structural’ factors or social policy. He writes: “There are only two causes for the historical and ongoing voting disparities between younger and older Americans. Either there is something wrong with young Americans as a group or there is something wrong with our voting policies. Either other swing voters are unreliable, or our voting system is unreliable. Either there is something wrong with people, or there is something wrong with policy.”

[25] An example: “Although I believe that values are socially constructed rather than God given…I do not believe that gender inequality is any more defensible than racial inequality, despite repeated efforts to pass it off as culture-specific ‘custom’ rather than an instance of injustice.” Mari Ruti, The Call of Character: Living a Life Worth Living, Columbia, 2014, p.36. In the same paragraph she says all values are socially constructed—but that her views of what constitutes injustice are not. This self-justifying, self-contradictory approach to justice is typical of our time.

[26] For more on the severe difficulties that Marxism, Postmodernism, and various forms of critical theory have with making any moral statements of value or truth, see the important work by Steven Lukes, Marxism and Morality, Oxford, 1985 and also see Christopher Butler, Postmodernism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford, 2002. Lukes, himself a Marxist from what I can tell, writes about the ‘Paradox’ or contradiction of Marxism: “On the one hand [Marxism claims] that morality is a form of ideology, and thus social in origin, illusory in content, and serving class interests; that any given morality…is relative to a particular mode of production and particular class interests; that there are no objective truths or eternal principles of morality; that the very form of morality and general ideas such as freedom and justice…[are] so many bourgeois prejudices, behind which lurk in ambush just as many bourgeois interests.” (Lukes is quoting from Marx and Engels here.) “On the other hand” Lukes goes on “no one can fail to notice that Marx’s and marxist writings abound in moral judgments, implicit and explicit.” (Lukes, p.3) Later post-structuralists and critical theorists–when speaking of morality as being “socially constructed” and yet continuing to make implicit moral claims that they do not treat as relative and constructed—participate in the same contradiction. For more on how all forms of modern secularism have “inadequate moral sources to support their high moral ideals” see Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, Harvard, 2007, chapters 15 “The Immanent Frame”, 16 “Cross Pressures”, 17 “Dilemmas I” and 19 “Unquiet Frontiers of Modernity”, pp. 539-773.

[27] Miroslav Volf, The Spacious Heart: Essays on Identity and Belonging, Trinity Press, 1997, 57.

[28] While I do not want Christians to wholly buy into any one of these secular accounts of justice, readers should not conclude that these four views are equally valid or equally flawed. They are not. I am not arguing for moral equivalence of all these views, although I realize my article could be read this way and that is the reason for this endnote. I certainly have my favorites among these four. I see some closer to biblical justice and others further away. But to answer the question, “With which of these views can Christians work best?” is beyond the scope of this essay.

[29] MacIntyre in his chapter comparing the Libertarian view of justice (Nozick) to the Liberal view (Rawls) shows that, in the end, the arguments come down to saying, “but I deserve this” or “but the poor deserve this”. However, as MacIntyre shows, no secular view can say such a thing. Secular views voluntarily forfeited such language and argument. In a universe in which we just appeared, not for any purpose, through a process that is basically violent, we cannot talk about anything being deserved or right or wrong. The most that secular thinkers can ever argue for is that, on some cost-benefit analysis that murdering people or starving the poor is impractical for some agreed upon end. Yet, as MacIntyre points out none of the adherents of these views can avoid such talk. They unavoidably “smuggle” in language of morality and virtue that their own view of the world cannot support. That should tell them something. See MacIntyre, “Justice as Virtue: Changing Conceptions” Chapter 17 in After Virtue, 249.

[30] For the basic ideas in this paragraph see Richard Bauckham, “Reading Scripture as a Coherent Story,” in Richard B. Hays and Ellen F. Davis, eds. The Art of Reading Scripture, Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2003, 45-55. I flesh these ideas out in Making Sense of God: Finding God in the Modern World, Penguin Books, 2016, Chapter 10: “A Justice That Does Not Create New Oppressors” 193-211.

[31] For the basic idea in this final section on Christianity and power I am indebted to Christopher Watkin. See his Michel Foucault, Presbyterian and Reformed, 2018.