There is no more urgent question for American Christians than this:

What is wrong with the American Christian church and how can its witness and ministry be renewed?

Virtually everyone agrees that something is radically wrong with the church. Inside, there is more polarization and conflict than ever, with all factions agreeing (for different reasons) that the church is in deep trouble. Outside the church, journalists, sociologists, and all other observers either bemoan or celebrate the church’s decline numerically, institutionally, and in influence.

Some do not see any way forward for the church at all. At the one end of the spectrum are those very conservative professing Christians who have denounced most of Christianity as apostate for many years. They are sure that there is no way back for the irremediably corrupt institutional church. At the other end are the most secular, who have high hopes that religion will die out across the world over the next generations. They simply want to “empty the pews.”

Neither outcome is likely—though, as in other cases, social media magnifies and gives the impression that such opinions are more representative and powerful than they are. The global Christian church is growing rapidly (as is Islam) and most demographers and social scientists do not see either religion in general or Christianity in particular fading away to a non-consequential force, even in the West. If that is the case, what should be done? How should the Christian church understand what is wrong and what a path to renewal could look like?

The best method for understanding the way forward is to begin by recounting the story of the American church’s decline. In this series, I will take two articles to do that, and then another set of articles to map out a possible path forward.

The Last Flourishing

The American church after World War II seemed to be strong and flourishing. In 1952, a record 75% of Americans said religion was “very important” in their lives. In 1957, over 80% said that religion “can answer today’s problems.” Church affiliation during the 1950’s jumped from 55% to 69%. [] [1] Robert D. Putnam and David E. Campbell, American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, Simon and Schuster, 2010, 87. From 1950 to 1960, the U.S. population went from 150 to 180 million, a record growth aided by the post-war “Baby Boom.” In the late 1950’s, almost one-half of all Americans were attending church regularly. This was the highest percentage in U.S. history. [] [2] See Robert Ellwood, The Fifties Spiritual Marketplace: American Religion in a Decade of Conflict, Rutgers U. Press, 1997.

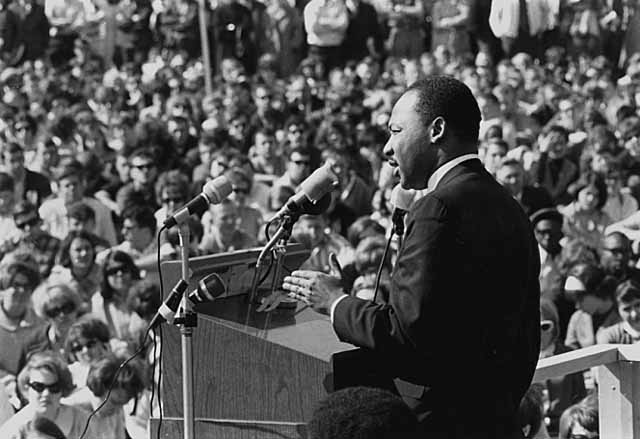

Another remarkable feature of this religious surge was how ubiquitous it was. Religion flourished, it seemed, in every class, race, region, and denomination. Catholicism seemed to finally be entering the cultural mainstream, no longer just a working-class or ethnic church. Archbishop Fulton Sheen had a large following on radio and television. The African-American Church took front and center in the great social changes of the civil rights movement, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. Even conservative white Protestants were on the upswing with the unprecedentedly successful ministry of Billy Graham who was himself part of a new alliance of organizations and leaders who sought to distinguish themselves from fundamentalism, calling their movement “evangelicalism.”

Mightiest of all was mainline Protestantism, consisting of the Methodist, Lutheran, Episcopal, Presbyterian, American Baptist, and the United Church of Christ (congregational) denominations. Their buildings were at the center of nearly all historic downtowns, their schools and institutions were of the highest prestige and their endowment funds were enormous.

The Decline of the Mainline

Yet this seemingly high water mark led almost immediately to unprecedented church decline that began first with the mainline denominations. From a high of 3.4 million members in the mid-1960s, the Episcopal Church declined to 2.4 million by the early 1990’s. In 2019, it recorded 1.6 million members. The mainline Presbyterian Church had 4.25 million members in 1965, but by 2000, they numbered 2.5 million and in 2020, 1.25 million. Other major denominations have shown more or less similar precipitous declines. By the mid 1970’s, it had become clear that something was afoot that had never happened before. “For the first time in [the] nation’s history most of the major church groups stopped growing and begun to shrink… Most of these denominations had been growing uninterruptedly since colonial times… now they have begun to diminish, reversing a trend of two centuries.” [] [3] Dean Kelley, Why Conservative Churches Are Growing: A Study in Sociology of Religion with a new Preface, Mercer University Press, 1996, 1.

Those words were written by Dean Kelley in his bombshell 1972 book, Why Conservative Churches Are Growing. Kelley was a legal scholar who worked for the National Council of Churches—the council of mainline Protestantism. He was not a conservative; he lobbied against prayer in public schools and served on the board of the ACLU. Yet Kelley’s criticism of the mainline church was searing.

In those early years of decline, Kelley heard mainliners complain that “people are just not as religious anymore,” but he responded:

Not all religious bodies are shrinking. While most of the mainline Protestant denominations are trying to survive what they hope will be but a temporary adversity, other denominations are overflowing with vitality, such as the Southern Baptist Convention, the Assemblies of God, the Churches of God, the Pentecostal and Holiness groups, the Evangelicals, the Mormons… Jehovah’s Witnesses, Seventh-Day Adventists, Black Muslims, and many smaller groups… [] [4] Ibid, 20-21.

Kelley’s Sociological Critique

So what was the problem? The appeal of religion, Kelley wrote, was that it provided ‘largest-scale meanings.’ These are not the genuine but small-scale meanings such as helping others in the neighborhood or volunteering for a good cause. Rather, largest-scale meanings enable people to face suffering and death with confidence and hope and to seek the long-term common good, making sacrifices for it, all because you know you are part of a “cosmic purpose.” The only “largest scale meanings that seem suitable to produce such results [are] those offered and validated by religion.” [] [5] Ibid, 43-44.

Kelley argued that conservative churches continued to focus mainly on spiritual needs and supernatural “largest-scale” cosmic meanings—the reality of God, the truth of Jesus’ resurrection, the power of the Holy Spirit for inward change, the efficacy of Jesus’ death for the forgiveness of sins, the eventual arrival of the kingdom of God.

Liberal mainline churches, on the other hand, had adapted heavily to modern secular thought. They rejected the concept of miracles, of being born again by the Spirit, of Jesus’ bodily resurrection, of a trustworthy Bible. They adopted, in Kelley’s words, “relativism… lukewarmness… individualism…” all of which he identified as “Evidences of Social Weakness”—that is, marks of a weakening community that cannot coalesce powerfully around a life of shared faith, meaning, forgiveness, love, and spiritual growth in God. [] [6] Ibid, 84-85. The mainline churches adopted the therapeutic view of the self and dropped traditional Christian ethical strictures around the use of sex and money. Kelley responded with what he called the “Minimal Maxims” for a strong religious body:

Those who are serious about their faith:

1. Do not confuse it with other beliefs/loyalties/practices, or mingle them together indiscriminately, or pretend they are alike, of equal merit, or mutually compatible if they are not.

2. Make high demands of those admitted to the organization … and do not include or allow to continue within it those who are not fully committed to it.

3. Do not consent to, encourage, or indulge any violations of its standards or belief or behavior by its professed adherents.

4. Do not keep silent about it [your faith], apologize for it, or let it be treated as though it made no difference, or should make no difference, in their behavior… [] [7] Ibid, 121.

So what was the ‘mission’ now of the mainline churches? Kelley said that these denominations had come to concentrate almost completely on political causes rather than focusing on leading people to faith and then building them up in their faith. They also moved beyond the simple call (that the church had done for centuries) for Christians to be ‘salt and light’ in the world, caring for their neighbors, working for a more just society, and helping the poor. Instead, the mainline churches identified themselves—and therefore Christianity—with particular political parties and social policies. The unique things that only the church could do had been abandoned and things that were better done by the liberal political parties were now seen as the main job of the modern denominations.

Kelley, though himself a political and theological liberal, predicted that churches that continued to turn themselves into political organizations would see continued decline. And, in hindsight, there was a warning to conservative churches not to do the same thing with the Republican Party that the mainline had done with the Democratic Party. Kelley has been almost completely ignored on all fronts. He received heavy criticism from the Left and, after a little enjoyable schadenfreude, conservative Christians did not take his warnings seriously. That is why most of the readers of this essay may have hardly heard of him.

Machen’s Theological Critique

Fifty years before Kelley wrote, a completely different kind of critique against the mainline church was published. In 1923, J. Gresham Machen published Christianity and Liberalism with a major New York publisher (Macmillan). A professor of New Testament at Princeton Theological Seminary, Machen wrote when there was no numerical or institutional decline as of yet. There was no diminishment or loss to be analyzed yet from a sociological viewpoint the way Kelley did fifty years later. Yet Machen took aim at the Protestant mainline because he saw it shedding its historic religious beliefs and faith in an effort to become acceptable to the modern world. He argued that—

The great redemptive religion which has always been known as Christianity is battling against a totally diverse type of religious belief, which is only the more destructive…because it makes use of traditional Christian terminology…[M]anifold as are the forms in which the movement appears, the root of the movement…is naturalism—that is, in the denial of any entrance of the creative power of God (as distinguished from the ordinary course of nature) in connection with the origin of Christianity. [] [8] J. Gresham Machen, Christianity and Liberalism, New Edition, Eerdmans, 2009, 2.

Protestantism knew that modern science would object to Christian “particularities”—all the main doctrines of the Christian faith as historically held, such as the virgin birth of Christ, the pre-existence and incarnation of Christ, the atonement on the cross, and of the bodily resurrection. In response, Machen observed: “the liberal theologian seeks to rescue certain of the general principles of religion, of which these ‘particularities’ are thought to be mere temporary symbols, and these general principles he regards as constituting ‘the essence of Christianity.’” [] [9] Ibid, 5.

Machen’s assessment was even more searing than Kelley’s. He argued that liberalism’s attempt to create a de-supernaturalized Christianity “has really relinquished everything distinctive of Christianity, so that what remains is in essentials only that same indefinite type of religious aspiration which was in the world before Christianity came upon the scene.” [] [10] Ibid, 6. The changes were no mere ‘tweaks’ or updates. They altered Christianity at the most fundamental level, turning it into something that was not Christianity at all.

There have always been religions in the world that aspired to a higher form of living, that provided various sorts of inspiring stories that encouraged a higher-toned life. All of these religions were forms of self-salvation through various ethical practices, religious observances, and transformations of consciousness. But Christianity was and is wholly different. It insists that we are saved not by what we do, but by what God in Christ has done for us in history—in his incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and ascension. Machen understood that if one loses a belief in the historical reality of these events, then whatever Christianity is left is now re-made into just another religion of works-righteousness. And that removes the main thing that differentiates Christianity from all other faiths. In his chapter on salvation, he writes:

If Christian faith is based upon truth [of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus], then it is not the faith which saves the Christian but the object of the faith….To have faith in Christ means to cease trying to win God’s favor by one’s own character; the man who believes in Christ simply accepts the sacrifice which Christ offered on Calvary. The result of such faith is a new life and all good works; but the salvation itself is an absolutely free gift of God….Very different is the conception of faith which prevails in the liberal church. According to modern liberalism…. salvation is thought to be obtained by our own obedience to the commands of Christ. Such teaching is just a sublimated form of legalism. Not the sacrifice of Christ but our own obedience to God’s law is the ground…of acceptance with God. [] [11] Ibid, 120-121.

As we have noted, Machen wrote when there were no signs yet of numerical or institutional decline at all. And his critique did not include a prediction of such decline—Machen believed that the changes were lethal to the actual life and mission of the Christian church, whether or not this led to changes in attendance and giving. [] [12] Ibid, 150-151. At the end of his book, he admitted he did not have any idea what the future held for the church. Machen refers to the entrance of paganism into the Christian church in the second century—a battle that was fought and won by the church fathers—and to the corruption of the medieval church, which resulted in the Reformation and the division of Christendom. Machen hinted that some kind of reckoning would come to such a massive change in the theology of the churches, but he did not guess how it would play out.

It is impossible not to see how Kelley’s analysis of mainline decline in many ways (despite the sharp difference in viewpoints) agreed with Machen’s. Machen said the church was abandoning the main things that were unique to Christian faith. Kelley agreed. Kelley, speaking sociologically, spoke of connecting people to “largest-scale meanings” while Machen, speaking theologically, spoke of connecting people vitally to God.

Instead, the church was becoming a social service agency and political lobbying bloc, performing functions that could be done far better by secular organizations. No wonder it was in decline. The mainline church was increasingly offering people nothing that the secular culture and its institutions could not offer. [] [13] In fairness to Machen, he, unlike Kelley, believed that the church’s jettisoning of historic doctrine was not just impractical and institutionally self-defeating, but wrong. It was a betrayal and should be opposed for that reason alone. If I want to work for inclusion and justice, there are lots of ways to do it. Why do I have to get up early on Sunday morning or connect to a Christian church with all its baggage in order to do that?

Marsden’s Cultural Critique

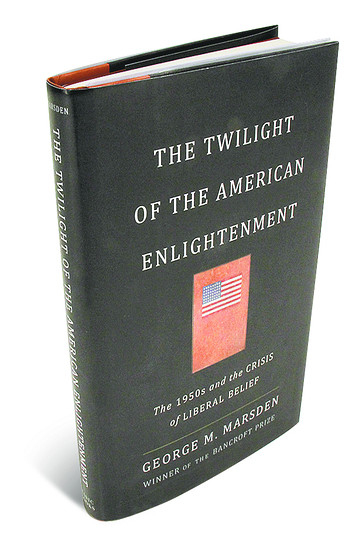

There was, however, a final reason for mainline decline that was not apparent until decades later. The historian George Marsden argues in The Twilight of the American Enlightenment that the Protestant mainline had allied itself to a secular moral consensus that was inherently unstable. When it began to give way, mainline Protestantism began to slide as well.

After World War II, America had emerged as the world military and economic power. Our population was growing rapidly as were our incomes and bank accounts. It all seemed to be a triumph of “American values.” There seemed to be unity about our shared moral standards. There was nothing like the ‘culture wars’ of the present—morality was seen as obvious and as a given.

But Marsden chronicles how the seemingly unified and optimistic 1950’s contained a strong undercurrent of doubt, that something was profoundly wrong with us. Leading intellectuals charged that materialism and popular culture were turning Americans into conformists, cogs in a great machine. [] [14] This is the burden of chapter 1 of George Marsden in The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s and the Crisis of Liberal Belief, Basic Books, 2014, 1-20. Many believed that the unprecedented prosperity had turned Americans into ‘cogs in an economic machine,’ de-personalized beings who did whatever it took to get ahead. “Hyperorganized commercial society and consumerism” was undermining our “true humanity” (42). Books by Eric Fromm, William Whyte and others countered that the antidote to stultifying conformity was the assertion of individual freedom—to be an authentic, self-determining, and self-fulfilled person (31). The answer, said many public intellectuals of the time, was to assert one’s individual freedom and become authentic, self-determining, and self-fulfilled persons. [] [15] Ibid, 86. Many of the most popular public intellectuals at the time were not philosophers, but psychologists, such as Gordon Allport, Carl Rogers, B.F. Skinner, Erving Goffman, and Rollo May. Despite their many differences, they shared the basic idea of Freud’s psychoanalytic tradition, namely, that people matured and became healthy as they escaped the irrational guilt, fears, and controls of traditional community and authority. To that they added a deep, particularly American, optimism that human beings could and would shape themselves for the better if given complete freedom to do so.

However, freedom was increasingly being defined as ‘autonomy,’ a word that meant literally to be a law unto oneself. Historically, human fulfillment and meaning was understood to be found not in a quest to find our own singular happiness, but in seeking the happiness of families and communities through relationships and roles in which the group’s common good was made more important than one’s individual self-interest.

But now by the late 1950’s and early 1960’s a steady stream of best-selling books, such as David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd, called Americans to be more authentic and self-determining, to not allow family or any local ‘subcommunities’ to dictate their values and purposes. We become full persons, it was said, only as we leave the moral prescriptions of others and discover our own. [] [16] See Marsden, chapter 2, “Freedom in the Lonely Crowd”, 21-42. The term “freedom” was becoming an almost wholly ‘negative’ term—a freedom only from. However, Marsden asked: “Once one was free from restrictive traditions or expectations, what was going to replace them as a basis for determining what was good for human flourishing?” [] [17] Ibid, 42.

Virtually the only major cultural figure to sound an alarm in the U.S. was the eminent writer and journalist Walter Lippmann. [] [18] It is worth noting in this context that Lippmann thought highly of Machen’s book Christianity and Liberalism. Also, C.S. Lewis, a respected literary scholar, but not really a factor in U.S. intellectual life, wrote The Abolition of Man in 1943, a book that anticipated the critiques not only of Lippmann, but of Alasdair MacIntyre and later Charles Taylor, all of whom argued that secular society has no adequate basis or source for its moral ideals. A recent excellent re-iteration of the critique is by Christian Smith in Atheist Overreach, Oxford, 2018. Smith explains that without either a basis in tradition, revelation, or natural law, atheist/secularists cannot provide a rational reason why one set of moral feelings should take precedence over another, nor can they provide a practical motivation for adhering to moral principles even when it entails major sacrifice. For another classic presentation of the argument, see Arthur Allen Leff “Unspeakable Ethics, Unnatural Law” Duke Law Journal, December, 1979. Lippmann was a non-religious Jew who was at the center of the secular liberal establishment. But in 1955 he wrote his last book, Essays in the Public Philosophy, which dismayed his peers. “His heresy was to say that his liberal colleagues were trying to build a public consensus based on inherited principle, even after they had dynamited the foundations on which those principle had first been established.” [] [19] Ibid, 44.

He charged that our liberal American values (whether fully executed or not)—equal dignity of all people, freedom of conscience, thought, and speech, government by consent, trust in science and reason—were not the deliverances of science. Originally, these American ideas were based on transcendent moral standards, a higher “universal order” that we could all recognize as the truth.

Lippmann was no theist, and so he was speaking more in the tradition of Aristotle. But he insisted that unless a society could recognize an objective moral order, a set of standards that were not merely produced by culture or our private feelings, there was no grounding for a public, shared social order. “If what is good, what is right, what is true, is only what the individual ‘chooses’ to ‘invent,’ then we are outside the traditions of civility.” [] [20] Cited in Marsden, 47. By that he meant that no one had ever tried to create a social common life on such a basis. Who is to say that one particular law is just and another unjust? Do we do it by majority vote? Then what do we say to Germany whose majority thought it was right to persecute and even destroy minorities?

Lippmann was right that our original “American values” originated in an agreement between Christians who believed these were the teachings of the Bible as well as Enlightenment thinkers who believed as the ancients in “natural law”—a transcendent, moral order in the universe that was discernible through human reason and reflection. But in 1955 the American modern liberal establishment was aghast at Lippmann. They reviewed his book negatively and pushed back, saying that returning to belief in God or natural law was dangerous and completely unnecessary. A “nondogmatic, relativistic, pragmatic” way of testing beliefs was the best. Our values are just things “we all know” that will benefit human beings best and will make most people happy. They are not rooted in God or a cosmic order. [] [21] See Marsden, chapter 3, “Enlightenment’s End? Building Without Foundations”, 43-67.

Interestingly, the leading public intellectual of mainline Christianity, Reinhold Niebuhr, also rejected Lippmann’s book. [] [22] Ibid, 53.

Niebuhr, just as Machen had predicted, had adapted the faith to secular science. He wrote that “we” modern Protestant believers “do not believe in the virgin birth and we have difficulty with the physical resurrection of Christ. We do not believe…that revelatory events validate themselves by a divine break-through in the natural order.” [] [23] Ibid, 118. There were things in the Bible that modern secular people could not accept, and liberal Protestants therefore rejected them too. The standard of truth, in other words, was not supernatural revelation, but instead secular practical reason. The Bible did not determine what was right and wrong in the secular, modern view—the secular modern view determined what was right or wrong in the Bible. So Niebuhr agreed with other critics that Lippmann’s call to return to religion or natural law was wrong and unnecessary. All rational persons could just agree that a commitment to democracy, human rights, individual freedom was simply reasonable.

However, as Marsden asks (and as Machen had argued decades before), what need then was there for the church at all?

The grand irony of that strategy was that, while Niebuhr himself used it effectively as a way to preserve a public role for the Christian heritage, its subjective qualities made the faith wholly optional and dispensable… One could simply bypass the theology and adopt the profound insights into human limitation that Niebuhr offered. [] [24] Ibid, 119.

The End of America’s Cultural Unity

Lippmann was right. Even as a relativistic, secular worldview had taken the place of the Christian/Enlightenment view, the older consensus on moral values was still maintained temporarily because of enormous common enemies—a Great Depression and two World Wars. These crises required self-sacrifice for one’s family and community merely to survive and necessarily muted the culture’s therapeutic and individualizing underpinnings. There was still great agreement across the political spectrum on what a good, moral life looked like. Love of country, sexual chastity, faithfulness, thrift and generosity, modesty and respect for authority, sacrificial loyalty to one’s family and relationships—nearly everyone believed in all of these even if there were plenty of deviations in actual behavior.

But by the late 1960’s such survival challenges were just memories, and as people followed the culture’s direction to discover truth within themselves, they began to come to radically different conclusions about what was right and wrong. American society began to splinter and has been doing so ever since.

The original Civil Rights movement led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. had pointed (as Lippmann had counseled) to a higher moral law. “What gave such widely compelling force to King’s leadership and oratory was his bedrock conviction that moral law was built into the universe.” [] [25] Ibid, 65. But by the time King was assassinated in 1968, very different forces were already at work. All the coming “rights” movements for women, gays, and other minorities modeled themselves in some ways (e.g. the protests and activism) on King’s movement, but the philosophical framework was completely different. Identity politics grounded claims for justice not in an objective moral order, but in their own group’s unique perceptions and experience. Individualism eroded traditional values such as love of country, loyalty to family bonds, and respect for authority. And many of these groups, especially those demanding sexual rights, had beliefs about morality at sharp variance with traditional western, Protestant ethics. The country began to break up into warring factions.

Why? No leading cultural figures could point, as Lippmann and MLK did, to a higher law, or to the Bible. The Protestant establishment had given up their ability to do that. Everyone had assumed that secular, pragmatic, common sense reasoning would come to an agreement on social mores. When that failed, there was no court of appeal or rationale available in any discussion of moral values. If someone called out injustice by saying: “What you are doing is wrong—because I feel it is wrong” there was no answer for the rejoinder “But I do not feel it is wrong—why then should your feelings about this be privileged over mine? What right do you have to impose your views on me?” Since our society had discarded any shared basis for moral values—religion and natural law—there was nothing left to unite us at all, no basis for a debate. As Lippmann argued, no society had ever sought to do this before, and he doubted it could be done.

And as the country began to break apart, mainline Protestantism began to slide. First it began to lose those who were coming to less straight-line, politically liberal conclusions. It lost political conservatives, but that was just the start. Later it continued to decline, because even the children of liberal Christians, as Kelley and Machen had pointed out, failed to see any real usefulness to the Christian church.

Ironically, Niebuhr saw that increasing secularism put the long-time American impulse toward rampant individualism on steroids. As religion declined and secularism grew, selfishness grew apace. [] [26] On how religion once balanced out American individualism, but has since lost its ability to do that – Robert Bellah, et al, Habits of the Heart: Individualism and Commitment in American Life, University of California Press, 2007. He spoke of the “self-glorification” encouraged by modern culture, which was leading people to use wealth and sexuality not just as good gifts, but as ways to create an identity. He spoke of the idolatries of secular liberalism (that deified human reason) and fascism (that deified the race and soil) and socialism (that deified the state). [] [27] Reinhold Niebuhr, “The Christian Church in a Secular Age”, in Robert McAfee Brown, ed. The Essential Reinhold Niebuhr: Selected Essays and Addresses, Yale University Press, 1986. But as Marsden adds, Niebuhr’s “chastening words regarding the human condition could be welcomed, but his generalized Christianity offered little to challenge most of the secularizing trends that he himself identified.” [] [28] Marsden, xxvi. Mainline Protestantism was no longer about radical conversion, about an encounter with a transcendent God and the reordering of the loves of the heart. It was about ethics and politics, and it had adopted too many of secularism’s assumptions to be any real challenge to it.

Conclusion

All the mid-20th century figures who assured us that pragmatic common sense and scientific reason could bring about a unified moral consensus have been proved terribly wrong. [] [29] We should add that the original Enlightenment thinkers have also been proven wrong—hence the contemporary claim that “the Enlightenment project has failed.” (See the writings of Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue, Whose Justice? Which Rationality? and Three Rival Versions of Moral Inquiry and, more recently and concisely, Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed) The original Enlightenment ‘project’ was to use reasoning apart from tradition and religion to discover a moral basis for a unified society. The current crisis of authority and knowledge in U.S. society is the older liberalism (Enlightenment/liberal Protestant consensus) being opposed by a progressive “successor ideology” that denies the basic concepts of free speech, individual rights and value-neutrality. There are currently no well-represented alternatives to these two public philosophies, though both Catholicism and Reformed Protestantism have the bases for models of society that re-introduce natural law and religion to the public sphere, yet allow for pluralism of belief and freedom of conscience. But Marsden’s last chapter argues that mainline Protestantism, the Religious Right, and the current secular progressivism have all failed to show any ability to combine religion with openness to other viewpoints. He offers an “Augustinian” option. See Marsden, Twilight, “Conclusion: Toward a more Inclusive Pluralism,” 151-178. The polarization in our society has become severe and the disagreements are about the most basic ideas of what human nature is and what human flourishing looks like. There is no longer any common set of “American values” or a unifying “American story.”

And the decline of mainline Protestantism, once the unofficial religion of America, was both a cause of and a result of this breakdown in American society. It both paved the way to the secularization of culture (rather than resisting it) and then became the victim of the same wave it had facilitated.

In light of the rightful critiques of Kelley, Machen, and Marsden, I believe that progressive mainline Protestantism cannot be the way forward for the American church. This is not to dismiss all the leaders and people who labor with genuine faith in the mainline congregations.

But the overall project of mainline Protestantism has failed. Today, in light of the discrediting failures within Catholicism and Evangelicalism (see the next article in Winter 2022) many are resurrecting the idea that Progressive Christianity—which is simply an extension of the mainline—is the best alternative. But the fundamental assumptions of mainline Christianity remain intact. It over-adapted to western secular culture 100 years ago and it is still doing so today. And as such, it can’t offer our society an alternative or counter-point, nor can it be the path to renewal for the American church.